Paula Rego: brushing aside repression

Lela playing with Gremlin (1984)

Paula Rego was a scathing storyteller. Her work tells tales of soaring fantasy, like those of her countryman, the novelist José Saramago; and tales of political repression, which make us think of the great print series of Francisco Goya; equally tales of social satire, so caustic they seem to slap convention in the face, rather like the biting narratives of William Hogarth; and, most wrenching of all, tales of psychological anguish, that sometimes reflect the work of Rego’s peers, Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud.

Portugal, in the years of Rego’s childhood and early adult life, isolated from the rest of Europe by the Salazar dictatorship, was poor, patriarchal, backward and deeply Catholic. Rego’s family were Anglophile liberals. Her father, an electrical engineer and affirmed anti-fascist, sent her to English schools to gain a different perspective, first at Carcavelos, outside Lisbon, and then a finishing school in the United Kingdom.

London, in the 1950s and 1960s, was able to offer Rego a wider choice of professional and social encounters. Studying at the Slade School of Fine Art, Rego met Victor Willing, her husband until his early death in 1988. In the 1960s, she exhibited with The London Group, which included among its members David Hockney and Frank Auerbach. Strikingly, Portugal’s most celebrated artist of the last 60 years spent the major part of her adult life in the UK, in 2010 being created a Dame and, in 2021, the year before she died, receiving a retrospective at Tate Britain.

Madame Butterfly

Despite all the years living in London, Rego’s work is deeply rooted in the specific cultural and political context of twentieth century Portuguese society, and in her own experiences as a child in a household of women: her mother, grandmother and aunt. This society is formal and traditional, with few clues provided to date a scene, emphasising an oppressive social immobility.

Rego’s work, charged with emotional or sexual tension, reflects the multiple levels of repression and convention of a society in which strongly built women, gazing out with defiant contempt, do their best to resist various authoritarian male figures – fathers, husbands, soldiers, priests. In some works women adopt degrading animal positions or are even actually represented as animals. Different generations of a family confront each other in power games; children witness scenes of manipulation or, surrounded by broken fetishistic toys, are themselves victims of implied abuse; the claustrophobic Salazar regime, often personified by the figure of a soldier, occupies both the pictorial and psychological space. Rego’s works can sometimes be read as fairy tales, though rather Grimm ones, with childhood overshadowed by adult frustrations and an unmentionable family secret lurking in every picture. Fear is never far.

Rego and Willing had three children together. Rego equally had several abortions. Women’s right to abortion was a central focus of her work over many years, most notably in a series of pastels of 1998 Untitled: The Abortion Pastels. This was the same year in which a referendum on whether to legalise abortion did not succeed in changing the status quo, perhaps because an insufficient number of women still did not ‘dare’ to come out of the house and vote for change.

The series was published in various Portuguese newspapers before a second referendum was held in 2007, and it is today considered the works had a decisive effect on this referendum’s historic outcome to finally legalise abortion. In Rego’s own view, this was her most significant artistic and human achievement.

Surrounded by the papier-mâché dolls with which she often populated her works, Rego, warm, charismatic and ironic, was in the most literal sense a colourful presence in her North London studio, her clothes an extrovert expression of an unconventional personality. The bright clothes, however, often covered dark thoughts. In addition to Willing’s slow health decline, Rego’s life was damaged by recurrent, sometimes severe depression – a suffering reflected in her work. After Willing’s death, Rego shared her life with a new partner, the writer and publisher Anthony Rudolf, although she acknowledged her real ‘marriage’ was to her work. The studio had become a refuge, in which she worked with her long-time assistant and model Lila Nunes.

The 2017 documentary Paula Rego, Secrets & Stories, directed by Rego’s son, Nick Willing, offers a mature exploration of Rego as woman, artist and mother. In 1990, Rego had been the first Associate Artist at the National Gallery, in London, a kind of artist’s residency. Although it seemed to her absurd to be asked to seek inspiration from a collection of works painted by men referencing a man’s world, she rose to the challenge and painted Crivelli’s Garden, a work which draws on the National Gallery’s paintings by Carlo Crivelli.

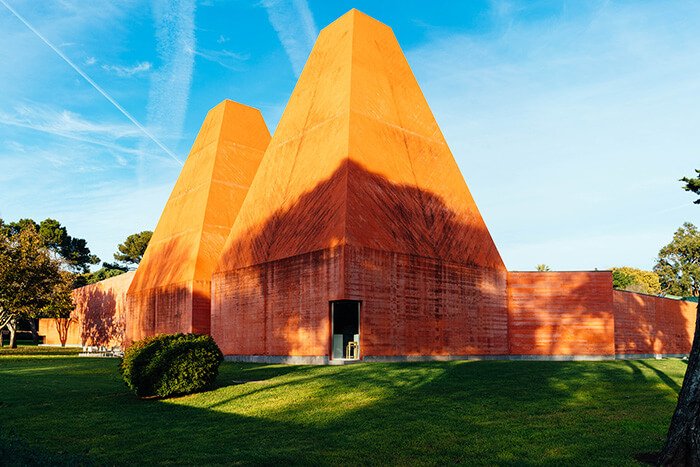

Recent decades have seen the emergence of an increasing number of women curators, art critics, gallery directors and, above all, artists. In the final years of her life, the woman who had challenged and criticised the system was welcomed in her home country with grateful affection. A museum in Cascais, designed by Portuguese architect Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Historias – a fitting name chosen by Rego herself – houses a collection of the artist’s paintings and prints. Today, Rego is remembered in Portugal as an icon, a woman who shifted society and attitudes. Perhaps, posthumously, Rego’s works will in the future command the prices her position as an artist calls for.

First published in Essential Algarve, November 2022