Portugal through the lens

Neal Slavin’s new exhibition captures the changes in the country from the Salazar era to our days

American photographer Neal Slavin has lived his entire life in Soho, New York, where he was born into a Jewish family of Russian immigrants. In 1968, Slavin visited Portugal on a Fulbright Fellowship, to photograph the work of an archaeological dig in Conímbriga. “I soon realised I’d rather photograph living people than dead relics,” he recalls. Anyone who has ever wondered what life was like under the repressive and isolationist Salazar regime, in the year in which, in the UK, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, will find some eye-opening answers in a remarkable exhibition of Slavin’s work, running until October 31 at Galeria WoW, in the cultural district of Vila Nova de Gaia (in Porto).

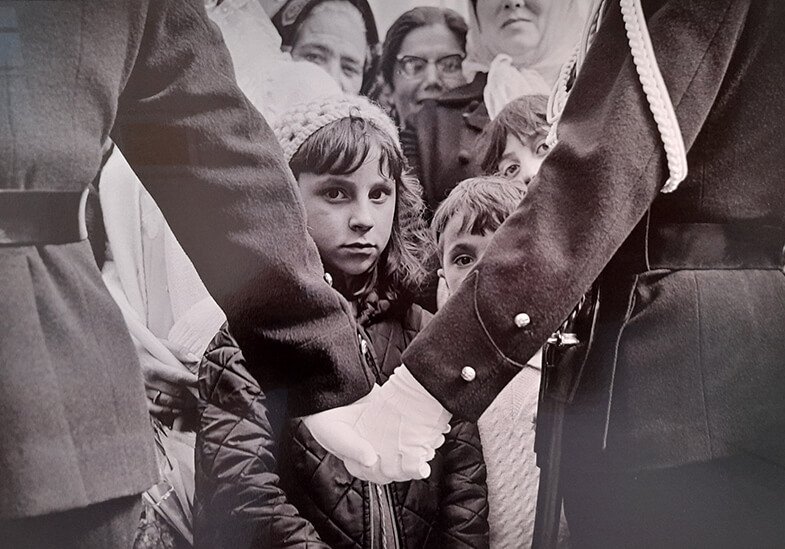

Slavin’s work of this period is in black and white, ideal to record a society that could just about manage grey, but which had absolutely no tolerance for colour.

The exhibition takes us beneath the decaying skin of the final months of the long Salazar dictatorship. Planned before the outbreak of the current European war, it is nonetheless a timely reminder of the precarity and precious nature of free societies. One of the many things frowned on by the Salazar regime, was the taking of photographs, potential subversive testimonies to truth… Creased faces, worn garments, insalubrious housing; bare-footed children playing in the street, the strict lines of a priest’s attire; two policeman holding hands, not in a gesture of friendship but to create a barrier; the formality of men in hats.

Galeria WoW, in the cultural district of Vila Nova de Gaia

The illiteracy rate in Portugal in 1970, a mere couple of years after Slavin’s visit, was 26% and only a tiny 0.9% of the population had received some form of higher education. Society was hierarchical and submissive, the middle class undeveloped, the Catholic church as omniscient as the regime itself.

“You start noticing people you speak to are constantly looking over their shoulder, to see if any informers are eavesdropping on the conversation,” Slavin describes. He remembers the “hopelessness” of living under a dictatorship.

In September 1968, Salazar fell into a coma, and the Estado Novo regime entered its epilogue period under Marcelo Caetano, before the whole apparatus was finally swept away by the April 1974 Carnation Revolution. Slavin returned to New York and resumed an increasingly successful career, with work appearing in publications such as Town & Country and The New York Times Magazine, and exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris.

A return to the country after almost 50 years: the new face of Portugal

After an absence of nearly 50 years, Slavin returned to Portugal in 2016. He was amazed by the transformation he found. Almost everything had changed: censorship replaced by freedom; stern, anxious expressions by openness and laughter. The images in the second half of the exhibition are, appropriately, in colour, reflecting a new mood of self-expression and hope.

In the intervening years, Slavin’s images had also shed some of the Modernist formalism of his earlier work and taken on a more abstract ‘painterly’ quality. For Slavin, the images in the second half of the exhibition celebrate Portuguese society’s victory over the despair of the Salazar years.

As Slavin explored Lisbon, simultaneously rediscovering old haunts and observing the new face of Portugal, driven, he readily admits, by nostalgia for the journey of his youth, he realised something had not changed. Portugal was still wrapped in a form of poetic melancholia. In a video in the exhibition, Mafalda, a young artist who has worked and studied in London, protests, “in Portugal, I’m stuck in this culture of melancholy…”

This is of course the celebrated Portuguese saudade, which no one has ever been able to translate, but which more or less expresses the Portuguese soul, forever longing for happier times. Depending on your point of view, this culture of feeling can either be deeply poetic and touching, or slightly exasperating, or even both.

The star contemporary Fado singer Mariza describes saudade as “sweet melancholy”. Interestingly, whilst some have turned their backs on Fado, the music of saudade, it is also enjoying a renaissance among the young.

“My admiration for the Portuguese soul is unshakeable”

The exhibition is completed by the documentary film Saudade: A love letter to Portugal, which Slavin finished shooting in Lisbon earlier this year, with a daily screening at 7pm.

Neal Slavin seems to draw a parallel between Portuguese notions of fate and lack of self-belief, and his own life-long tendency to fearfulness and disavowal of his significant accomplishments. He is certain where he stands on one thing though: “My admiration for the Portuguese soul is unshakeable.” For this writer, this exhibition of Neal Slavin’s photographs is a wonderful affirmation of freedom.

Follow Neal Slavin‘s work.

First published in Essential Algarve, August 2022